A new approach to ECS APIs

Let’s talk about a different approach to ECS I have been rumbling about lately. Well, specifically, about how we query entities, manage dependencies and access/modify data.

What is ECS you ask?

Fair question! ECS (as Entity-Component-System) is an architectural pattern based on DOD (data-oriented design), where you have three main elements:

- Entities: They are just an identifier and don’t hold any data.

- Components: Structs of data associated with a single entity (1 entity can have 1 component of each type). They don’t have any code/logic.

- Systems: Functions executed operating entities and components.

I could explain ECS in greater detail, but there are plenty of resources online already that will do a better job than me. This talk is a good start, and for more resources, you can also read this.

I personally also like to consider Utilities as the forth secret child of ECS. Utilities are functions that can be reused between systems. Any code that is not part of a system is a utility. One example could be hierarchy where we can add, remove, or transfer children from entities from multiple systems.

Current approach to ECS APIs

Now that we know what ECS is and the basics of how it works, let’s talk about how we could improve it.

In most ECS libraries I have used so far, there is always the concept of a view, or a filter. This is a tool that allows fast iteration of entities following a set of conditions. You can say, for example, “iterate all entities with ‘Player’ and ‘Movement’ components, but ignore those with ‘Frozen’ component”.

Implementation details may differ, but I will be using using the popular library entt as an example (it’s great, check it out). In this library, a “view” caches pools from the world when it is created, and uses them to check for entities matching some included and excluded components.

Problems sharing code

So lets make an example with entt where we move agents (a system):

void MoveAgents(entt::registry& registry, float deltaTime)

{

// We create a view matching all agents with movement and transform components

auto view = registry.view<const Agent, const Movement, Transform>();

// We iterate all entities in the view

for(Id entity : view)

{

// We get components and apply position based on velocity

const auto& movement = view.get<const Movement>(entity);

auto& transform = view.get<Transform>(entity);

transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

}

}

Okay, so far, we are just fine. But what if we have props that can move? But only when they are enabled.

void MoveProps(entt::registry& registry, float deltaTime)

{

auto view = registry.view<const Prop, const Movement, Transform>();

for(Id entity : view)

{

const auto& prop = view.get<const Prop>(entity);

if (prop.isEnabled)

{

// Can we reuse this?

const auto& movement = view.get<const Movement>(entity);

auto& transform = view.get<Transform>(entity);

transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

}

}

}

Well, we get some duplicated code, we could export this into a utility. But how?

If we wanted to share code as utilities, we would be extremely limited, specially if we want to track which data we are reading and writing, which is crucial for scheduling (more on that later).

// We could use references, but it's not very practical since we need to get the components outside anyway

void ApplyMovement(const Movement& movement, Transform& transform, float deltaTime)

{

transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

}

// We could pass the registry, but then we lose the fast access to pools from views.

// Also, we do not know from outside which components we are reading and writing

void ApplyMovement(entt::registry& registry, float deltaTime)

{

const auto& movement = registry.get<const Movement>(entity); // Accessing component directly through world is slow

auto& transform = registry.get<Transform>(entity);

transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

}

// We could pass the view as a template parameter.

// But templates need to be declared where they are used, meaning all shared functions will need to be most likely on a header.

// To that, you add different views for the same function, and you get slower compile times.

// Outside of templates, Views also are not intended to control access, and they can not do all the things you can do with the world.

template<typename View>

void ApplyMovement(View view, float deltaTime)

{

const auto& movement = view.get<const Movement>(entity);

auto& transform = view.get<Transform>(entity);

transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

}

Along with the problems sharing code (utilities) between systems, you will also have a really hard time tracking dependencies as your project grows if you want to do any sort of scheduling.

Problems scheduling

As I mentioned in the previous step, scheduling is a huge problem, and we should simplify it.

Scheduling helps us organize hundreds of system functions to execute safely in multithreading. To achieve that, we need to know where we read and modify components:

- We can safely read components of the same type from many threads at the same time.

- We can’t safely read components of the same type while any other thread is writing them.

We can, of course, schedule by hand, but this quickly becomes unmaintainable. That’s why there are many ways to automate it. But, as I said, you need to be able to know what you are doing inside a function from outside, or this won’t be possible.

// If we pass around the registry, we don't know our dependencies

// We don't know which components this function is accessing and modifying

void MoveProps(entt::registry& registry, float deltaTime) {}

Problems controlling data-flow

One of the points of DOD is that all code serves a single purpose: It converts data (input) into other data (output). “It’s all about the data.”

Having a view that we mostly only iterate is limiting us if we want to do proper algorithms where we use multiple steps to (efficiently) operate data.

Fixing the problems

Lets see what we need:

- We need to be able to easily share code

- We need to express dependencies when reading and writing components, allowing us to schedule

- We need to be able to apply complex data flows, allowing more cache and cpu friendly code

- It has to be blazing fast

- Errors must be simple and straight forward …proceeds to look at templates with disapproval

I experimented with a solution to this for a while and ended up implementing it in Rift. This solution I came up with solves all the points above, so let’s have a look rebuilding the previous examples with it:

// We pass an Access with the types we can write, and those we can only read (const)

void MoveProps(TAccess<const Prop, const Movement, Transform> access, float deltaTime)

{

for(Id entity : ListAll<Prop, Movement, Transform>(access))

{

const auto& prop = access.Get<const Prop>(entity);

if (prop.isEnabled)

{

// Can we reuse this? Yes

//const auto& movement = access.Get<const Movement>(entity);

//auto& transform = access.Get<Transform>(entity);

//transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

// So, lets reuse it

ApplyMovement(access, entity, deltaTime);

}

}

}

// The parent access (MoveProps) must have these components.

// If it doesn't, we will get proper errors telling us what's missing.

void ApplyMovement(TAccess<const Movement, Transform> access, Id entity, float deltaTime)

{

const auto& movement = access.Get<const Movement>(entity);

auto& transform = access.Get<Transform>(entity);

transform.position += movement.velocity * deltaTime;

}

Access

A access represents a set of components for efficient access and dependency tracking. It also can’t be directly iterated (by design). We have other tools for that.

- It is very cheap to copy (only a pool pointer copy for each component type)

- It provides instant access into component pools

- Extremely simpler and less template-heavy than views

- Can be constructed implicitly from the ECS world or other bigger accesses.

Access can have two flavors. Compile-time assisted TAccess<Types> or runtime based Access

It also makes sense to pass them as const reference to functions. They are cheap to copy yes, but we might not need to do it at all. That’s why I added an alias TAccessRef<Types> which is essentially the same as const TAccess<Types>&. It’s just easier to write.

Filtering entities

If a access can’t iterate on its own, how do we do it?

Iteration is done by creating and modifying lists of ids:

ListAll<Types>(access): Returns all entity ids containing all the provided components.ListAny<Types>(access): Returns all entity ids containing at least one of the provided components

Then we can also apply new filters like excluding components:

RemoveIf<Types>(access, ids): Exclude entities not having a componentRemoveIfNot<Types>(access, ids): Exclude entities having a component

It should be mentioned that these functions don’t ensure the order is kept by default (for performance), but we can use their counterparts for that:

RemoveIfStable<Types>(access, ids): Exclude entities not having a componentRemoveIfNotStable<Types>(access, ids): Exclude entities having a component

The potential of this is that we are just operating a list of indexes, and we are not limited by the functions above on what we can do. Its just “filtering” lists of ids.

One example could be in Rift, where the compiler precaches two lists, one for classes and one for structs:

TArray<AST::Id> classes, structs;

AST::Hierarchy::GetChildren(ast, moduleId, classes);

AST::RemoveIfNot<CType>(ast, classes);

structs = classes;

AST::RemoveIfNot<CClassDecl>(ast, classes);

AST::RemoveIfNot<CStructDecl>(ast, structs);

As you can see, it is filtering different components to finish with those two lists of types.

It also shows how filtering can also be done directly from the world (ast in the example) without an access. You wont get the benefit of cached pools, but it will still be really fast to iterate:ListAll<Types>(world) RemoveIf<Types>(world, ids) RemoveIfNot<Types>(world, ids)

Performance

I mentioned many reasons why this style of API is attractive, but there is another one. It is fast.

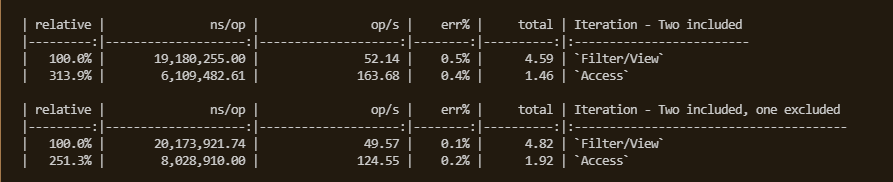

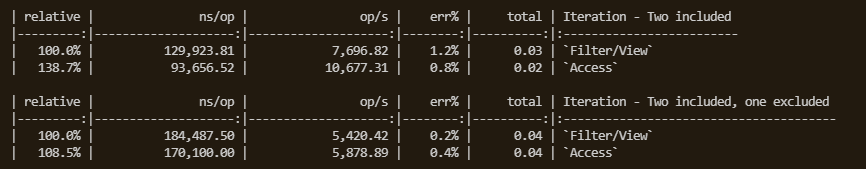

When I implemented accesses for Rift, I already had filters (very similar to entt’s views). So I took the chance to do a one to one comparison with the following results:

In debug access filtering gets up to 3 times faster iterating than views.

While in release the difference is tighter, between 35% to 50% faster in most runs.

Should be noted that this benchmark runs an empty iteration loop. For views, this means their pool checks are very close in execution. In other words, it is their ideal scenario. It is unrealistically in their favor. However, they seem to run slower. Why is that?

Why is it faster?

Unlike views, accesses don’t need to find their pools, again and again, every time they get created. Most of the time, a access is created from another, which is literally just copying the relevant pool pointers.

However this is not where most of the performance benefit comes from.

It comes from the fact that, while in views, each entity is checked at once against all the pools to filter, with ListAll all ids are checked pool after pool:

Views

- Iterate all ids in smallest pool

- Check that the id has components A, B, C

Access Filtering

- Get all ids from smallest pool

- Remove those that don’t have component A

- Remove those that don’t have component B

- Remove those that don’t have component C

This uses a single pool and its hash-set at a time, making it more cache-friendly.

I hope this post was not too dense. It is quite a specific topic, after all.

Consider having a look at Rift. It would be incredibly helpful to get your ideas, feedback and/or code contributions!